This is part of my ongoing series on reading the Western Canon. See here for an introduction to the series.

Although Bloom’s ‘core 26’ authors start with Shakespeare (and chronologically starts with Dante), his full list of books in the Canon starts with ‘The Theocratic Age,’ with works spanning from The Bible to The Iliad to Beowulf (the full list can be found here). Although none of these authors are among the ‘core 26’, they seemed important to read to understand later works of the Canon. So, I set out to read a handful of these books, mostly ones where I recognized the author or title. Alas, I read these before I endeavored to seriously blog about them, so my notes are not as fleshed out as I would like. Still, I will write my memories and thoughts on all of the books that I have read. With that in mind, I hope you enjoy my reviews and interpretations of some of the oldest literature in The Canon.

Today: Homer.

Homer - The Iliad

Starting this journey with Homer was simply wonderful. Before starting, I knew the gist of both of the Iliad and Odyssey, but I had never read either. As per Bloom’s recommendation, I went with the Lattimore translation of The Iliad. (As an aside, one of the great advantages of Bloom’s book is his translation recommendations. Translations can very easily make or break a book experience, and so far, Bloom has not done me wrong in his suggestions.)

The first thing that I was struck by while reading the Iliad was its brutal violence. I wasn’t expecting such vivid descriptions of brains and viscera, but I appreciated the details for making the battles so ‘real’ and easy to imagine. Further, I noted the Iliad’s readability. I had feared it would be a slog, but I actually didn’t find it too hard to get through. There are a few passages and chapters that simply list various families or tribes and how many soldiers belong to each, but I found these easy to simply skim through while enjoying the lofty prose.

As an aside, I think this is related to one of the key reading skills I have learned while working through some of the longer titles in the Canon: don’t try to remember everything. It’s simply impossible to remember or write down every beautiful phrase or detail without ruining your overall enjoyment of the work. It’s fine if you only remember major plot points and characters, or barring that, even just remembering how the book made you feel. I think some people are afraid of starting these books because of their length and complexity, as if the only way to get something out of great literature is the ability to pass a test on it afterwards. While writing a few bullets down is helpful for remembering what you liked about a book, trying to write down everything will only hurt your experience and make you more likely to give up.

In The Iliad, nearly every character, no matter how small, gets at least a few lines describing their life when they inevitably meet death on the battlefield. This device really hammers home the brutal consequences of battle, as you’re forced to read about so-and-so’s five sons and daughters and his beautiful herd of cattle and his hoard of treasure won in faraway lands, and how all of that is useless when you’re stabbed in the neck by a Trojan. At the same time, it memorializes the Greeks as the story goes along, and the combatants make clear that they know their deaths are glorious and noble. It’s as if Homer heard about the battle from the children of the combatants, and the children were sure to let Homer know that their dad was a noble man cut down in the most noble of pursuits.

The prose is filled with nature-based similes and metaphors: Greeks crash like waves upon the Trojan army and the Trojans shout like wildfowl ‘as when the clamor of cranes goes high to the heavens.’ There’s many breathtaking passages where entire nature scenes are described to give detail to men’s actions; for example: (Book Three, lines 10-14):

As on the peaks of a mountain the south wind scatters the thick mist,

no friend to the shepherd, but better than night for the robber,

and a man can see before him only so far as a stone cast,

so beneath their feet the dust drove up in a stormcloud

of men marching, who made their way through the plain in great speed.

It’s almost like being transported into a short story for a few lines before being dragged back into the slaughter. This happens incessantly, and it makes for simply incredible reading.

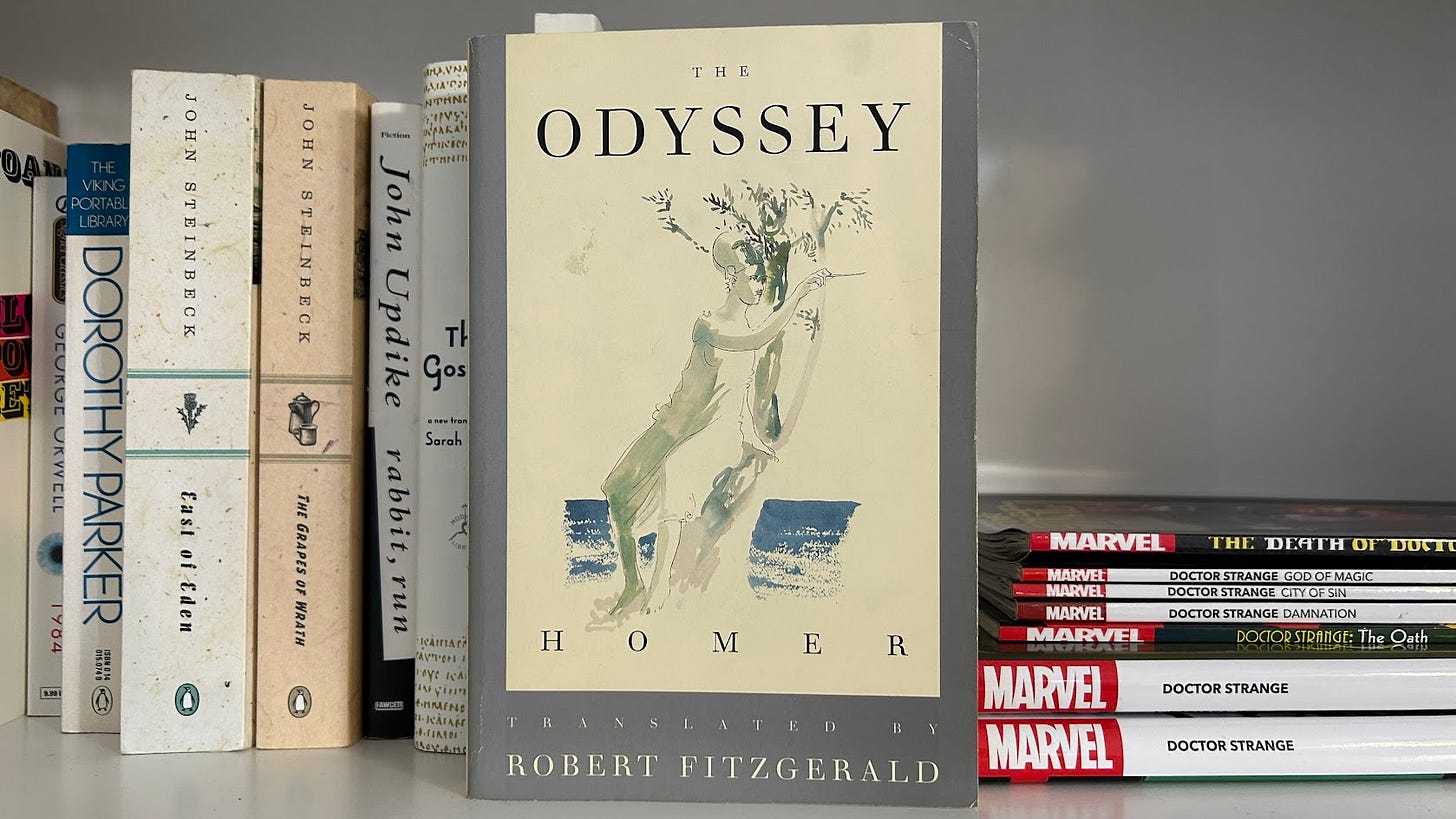

Homer - The Odyssey

It’s been said that The Odyssey is the world’s first novel (I heard it from Russ Roberts, host of the excellent Econtalk podcast, but he may have been quoting). Where The Iliad is epic, brutal, and focuses only on a few days of a monumental battle, The Odyssey is a sprawling, yearslong tale that reads like an adventure movie. I went with Fitzgerald’s translation, again at Bloom’s recommendation, and thoroughly enjoyed it. I actually found that each translation fit its respective book quite well - Fitzgerald’s Odyssey is more casual and adventurous, while Lattimore’s Iliad feels grand and ostentatious, more fitting for the formal and intense nature of the work.

Reading The Odyssey was indeed like reading a novel. I found myself wanting to know what happened next, eagerly turning each page. Some of my favorite passages were the detailed depictions of feasts. Each feast felt like an important ritual to take time and savor the moment. My favorite example of taking time to savor food and wine comes in Book VX, lines 475 through 489. Here, Eumaios (a poor swineherd on the fields of Ithaka) and Odysseus are talking, and after Odysseus takes an interest in Eumaios’ life story, we get this marvellous response:

The master of the woodland answered: “Friend,

Now that you show an interest in that matter,

attend me quietly, be at your ease,

and drink your wine. These autumn nights are long,

ample for story-telling and for sleep.

You need not go to bed before the hour;

sleeping from dusk to dawn’s a dull affair.

Let any other here who wishes, though,

retire to rest. At daybreak let him breakfast

and take the king’s own swine into the wilderness.

Here’s a tight roof; we’ll drink on, you and I,

and ease our hearts of hardships we remember,

sharing old times. In later days a man

can find a charm in old adversity, exile and pain.”

I struggle to describe just how incredible I find this passage. It perfectly conveys the 2:00 AM bonfire with friends, the staying for one more drink at a late happy hour, the dorm-room discussions before waking up early for class. It’s funny, too, because I didn’t think that my favorite passage from The Odyssey would be about two old men reminiscing in a hut in the wilderness. I suppose that’s part of why we read these great works, instead of just reading summaries or analysis. It’s not all about the ‘takeaways’ and ‘major themes.’

I think my only criticism of the Odyssey as an aesthetic work was its rather slow final arc. After Odysseus lands on Ithaca, there is a long period of waiting around before he reveals himself. While the dramatic irony is nice for a time, after a while I felt like I was just flipping pages until he finally reveals himself. Of course, that moment is immensely satisfying - the entire story builds up to Odysseus taking back what’s his and reuniting with his family.

Final thoughts

I found both The Iliad and The Odyssey to be engrossing reads, and would recommend them to anyone who enjoys reading. There’s a special magic, too, in reading some of the oldest works around, having been first composed around 700 BCE. These books have been enjoyed throughout the world for thousands of years, and there’s a good reason for it.