The Theocratic Age: Beowulf

This is part of my ongoing series on reading the Western Canon. See here for an introduction to the series.

Although Bloom’s ‘core 26’ authors start with Shakespeare (and chronologically starts with Dante), his full list of books in the Canon starts with ‘The Theocratic Age,’ with works spanning from The Bible to The Iliad to Beowulf (the full list can be found here). Although none of these authors are among the ‘core 26’, they seemed important to read to understand later works of the Canon. So, I set out to read a handful of these books, mostly ones where I recognized the author or title. Alas, I read these before I endeavored to seriously blog about them, so my notes are not as fleshed out as I would like. Still, I will write my memories and thoughts on all of the books that I have read. With that in mind, I hope you enjoy my reviews and interpretations of some of the oldest literature in The Canon.

Beowulf

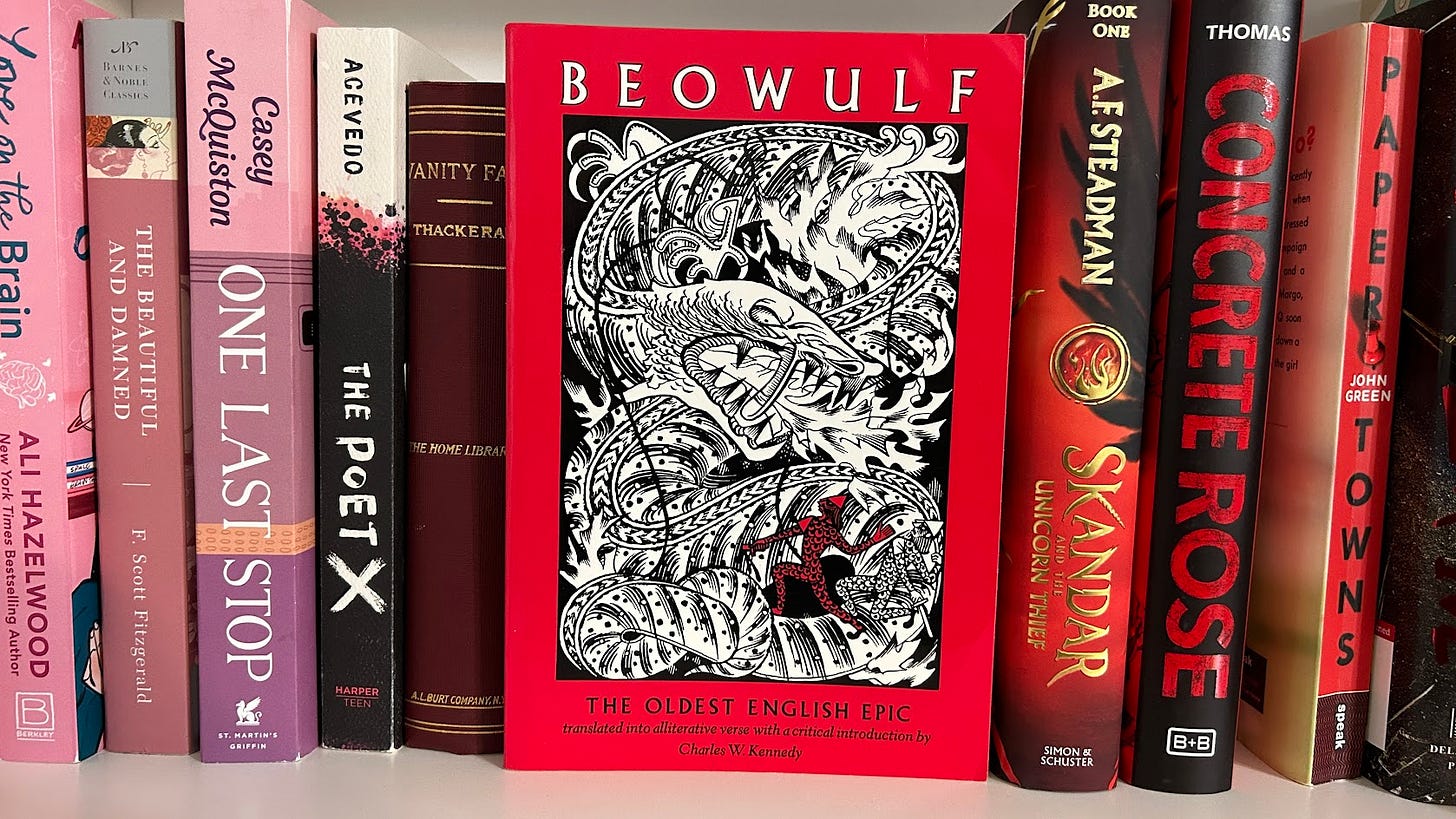

Beowulf was written around 1000 AD, making it one of the oldest surviving pieces of English literature. It’s something of a miracle we have access to it at all, as it only exists in a single manuscript, and that manuscript was damaged in a fire in 1731. Fortunately, the vast majority of the text survived, giving us a glimpse into ancient folklore. I used the translation by Charles W. Kennedy, as recommended by Bloom, and thoroughly enjoyed it.

Beowulf is a short, simple, and powerful story about a viking killing monsters. Really, that’s all you need to know. It’s filled with classic themes of valor, sacrifice, and honor. Of course, these themes feel so classic largely because of the influence of Beowulf itself! It’s a rather strange feeling to read something and think “ah, I’ve heard this a thousand times,” and then realize that the book you’re reading is the ur-legend itself.

Something I didn’t anticipate was the huge Christian influence and motifs throughout the story. Sure, everyone knows Grendel is the big bad monster, but did you know Grendel is actually a descendant of Cain? I certainly didn’t, and I find that it adds an excellent depth and meaning to the story.

The Intro

Beowulf may win the award for best opening passage in any story, ever:

Lo! we have listened to many a lay

Of the Spear-Danes’ fame, their splendor of old,

Their mighty princes, and martial deeds!

Many a mead-hall Scyld, son of Sceaf,

Snatched from the forces of savage foes.

From a friendless foundling, feeble and wretched,

He grew to a terror as time brought change.

He throve under heaven in power and pride

Till alien peoples beyond the ocean

Paid toll and tribute. A good king he!

First of all, the simple and emphatic call-to-arms ‘Lo!’ is just wonderful. The story starts as all campfire stories do, with a call for everyone to stop talking and pay attention. I might start every one of these blog posts with ‘Lo!’ from now on. Recently, a new translation by Maria Dahvana Headley has rendered this opening completely differently, amping up the bombast even more:

Bro! Tell me we still know how to speak of kings! In the old days,

everyone knew what men were: brave, bold, glory-bound. Only

stories now, but I’ll sound the Spear-Danes’ song, hoarded for hungry times.

How audacious can you get, turning the first line of a classic to read ‘Bro!’ I think it’s wonderful, and will probably pick up a copy of this translation soon and give it a go. Read more about Headley and her translation here.

The second thing I’d note about this intro is the phrase immediately after “Lo”: “we have listened to many a lay of the Spear-Danes’ fame.” I love this in media res feeling. Haven’t you heard all of the stories about the Spear-Danes? No? Well, keep reading and find out! This is also interesting because when Beowulf was first composed, this was literally true for the audience and not a narrative device. Everyone in that time had listened to many a lay of the Spear-Danes fame. Also, take a moment to actually say the first two lines out loud, and appreciate the masterful job that Kennedy has done in crafting the poetry here. “Many a lay of the Spear-Danes’ fame” flows beautifully off the tongue.

What can we learn from Beowulf?

Besides being a thrill to read, can we take anything away from this story? Certainly we can keep in our minds the heroism and bravery displayed by the title character to his dying breath. We can also reflect upon the advice Beowulf himself receives about growing rich:

[he has] An ample kingdom, till, cursed with folly,

The thoughts of his heart take no heed of his end.

He lives in luxury, knowing not want,

Knowing no shadow of sickness or age;

No haunting sorrow darkens his spirit,

No hatred or discord deepens to war;

The world is sweet, to his every desire,

And evil assails not - until in his heart

Pride overpowering gathers and grows!

Here, and older man advises Beowulf on the dangers of living a life of sheer comfort, without any strife, and how that comfort leads to pride and arrogance. Again, a very Christian theme, and expressed beautifully in this passage.

The end of the Theocratic Age

With Beowulf completed, we’re out of the Theocratic Age and into the Aristocratic Age. We’re also into the core 26 authors of The Canon, and first up is Shakespeare. I’ve been reading through Shakespeare for the past few months, and can’t wait to share some of my thoughts with you.